Future impact of

Space Debris on Global Industries

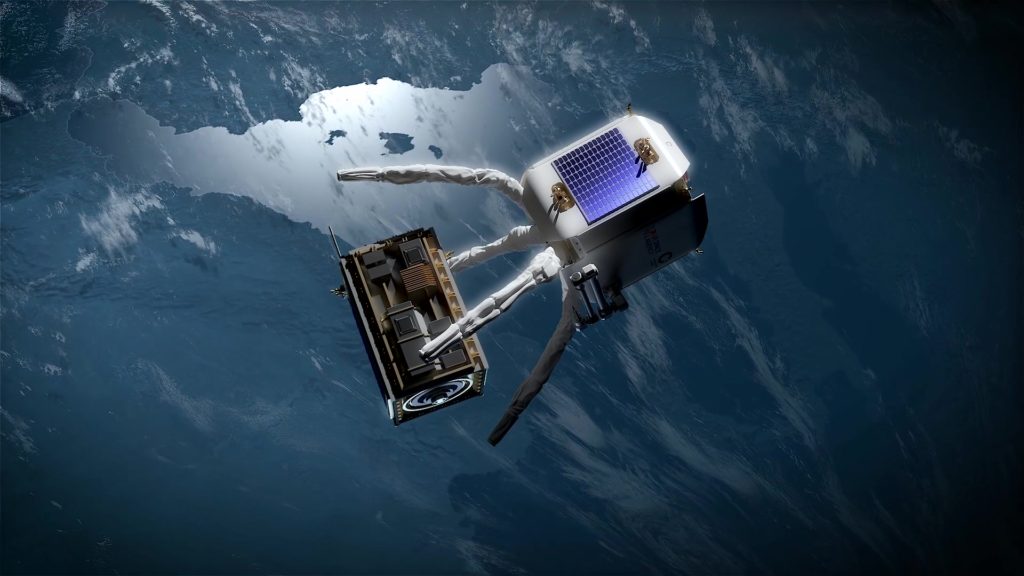

Artistic impression of the CLEAR Mission in orbit, funded by the UK Space Agency.

© ClearSpace

// 2023-DEC-22

The Troubled Orbits

Like other forms of debris in terrestrial and marine environments, space debris prompts questions about how well we look after our environment, and what we can do to be better custodians in the future.

Although advanced technical societies have come to increasingly rely on space based infrastructure, they have, so far, failed to meaningfully address the scale of accruing orbital debris. Only very recently has the awareness of space debris as a severe risk to both space and Earth infrastructures increased within the space community.

With the commercially driven “New Space age,” space debris is increasingly framed by space policy makers as a sustainability risk: private space entrepreneurs, have been adding to the large pile of twentieth-century space debris by launching unprecedented numbers of new satellites into orbit.

Although the notion of a vast universe is persistent, orbits, the “paths” on which satellites encircle the Earth, are far from endless. As contemporary societies largely depend on functioning satellite networks for data transfer, communication and navigation services, and climate and crisis monitoring, space debris is understood as a threat to planetary and orbital infrastructures.

For some, the congested orbits might even put an end to ideas of escaping our planet for other places in the cosmos, as safe launches of future spacecraft would be hindered by space debris.

It becomes an absolute necessity that the Wall-E predicted orbital dystopia remains a fictional fate envisioned by Pixar animators, and not a circumstantial rendering of the future for humanity’s presence in space.

Debris in Space

Although there is an emerging body of work that provides a valuable point of departure for exploring outer space as a convergence of scientific, technical, political, and cultural activities, space debris and the issue of crowded orbits have not been sufficiently empirically addressed.

Beginning with the launch of Sputnik in October 1957, from commercial communications satellites to the International Space Station, artificial objects populate the space around our planet.

In the past several decades society has benefited from these orbital advancements and continues to become more and more reliant on the technology orbiting Earth. Some of the major fields which increasingly rely on satellite services are:

- Financial Industry

- IoT

- Mass Media and Communication

- Aerospace Industry

- Construction Industry

- Agritech

- Defence Services

- Launch Industry

- Energy Industry

Parallel to these, contemporary culture revolves around access to the internet, television, cell phones and GPS – all of which utilise satellites for communications or positioning. With humanity’s ever-increasing presence in space, however, comes an ever-increasing presence of space debris – presenting a threat to satellite functionality and safety .

Every satellite that is launched into orbit is accompanied by a plethora of used rocket motors and spent fuel tanks. Antiquated satellites explode from residual propellant pressure or old batteries, sending fragmented pieces of junk tumbling into the same orbital lanes employed by operational spacecraft and crewed space missions.

With many countries fostering new space programs and numerous nations already launching satellites, the orbital debris issue is predicted to only get worse in the coming years.

Now the questions which need immediate answers are: Who gets to make the rules? Who becomes the garbage collector and who becomes the space traffic controller? The more populated orbits become, the more dangerous they are for other satellites in the future.

You can read more about these in the next blog of our series soon.

A Joint Mission: The UK Space Agency And ClearSpace

The UN mitigation guidelines are a positive step towards safer orbital regimes, but to ensure that humanity’s presence in space can continue, more priority has to be placed on protecting Earth’s satellites.

Advanced space missions require emphasis on space situational awareness which provides debris tracking and fragment simulation so operational vehicles can avoid the fragments already in orbit. Higher quality radar and optical instruments that can track smaller objects may be required to minimise the discrepancy between debris that can be avoided (10 cm) and debris that can be shielded (1 cm). At the same time there is a need to actively eliminate the present debris from orbits.

ClearSpace is leading a first-of-its-kind mission which is oriented towards the goal of removing two derelict satellites (which have been inactive for more than 10 years), analagous to a road based recovery vehicle, and is called “Clearing of the LEO Environment with Active Removal” (CLEAR).

These objects are predicted to stay in orbit for a century before they naturally re-enter the atmosphere and are located in a very congested region of LEO, above 700 km altitude, endangering the space environment and the safety of space operations. Previously chosen by the European Space Agency (ESA) to lead the first ever mission to remove debris from orbit, ClearSpace-1, now mission CLEAR, has been funded with £2.2M by the UK Space Agency, to proceed with its design phase which will last until the end of 2023.

The UK is actively engaging in international efforts to clean up space debris being the largest investor in space safety in the European Space Agency.

However, more international focus needs to be placed on preventing future fragmentation events to avoid polluting Earth’s populated orbital regimes.

Existing concepts to remove orbital debris are not entirely feasible and the increasing threat of fragmentation poses a substantial hazard to current and future crewed and uncrewed space missions. Though the United Nations has created guidelines to mitigate orbital debris generation, fragmentation events continue to occur and a stronger international focus on avoiding future satellite collisions is needed.